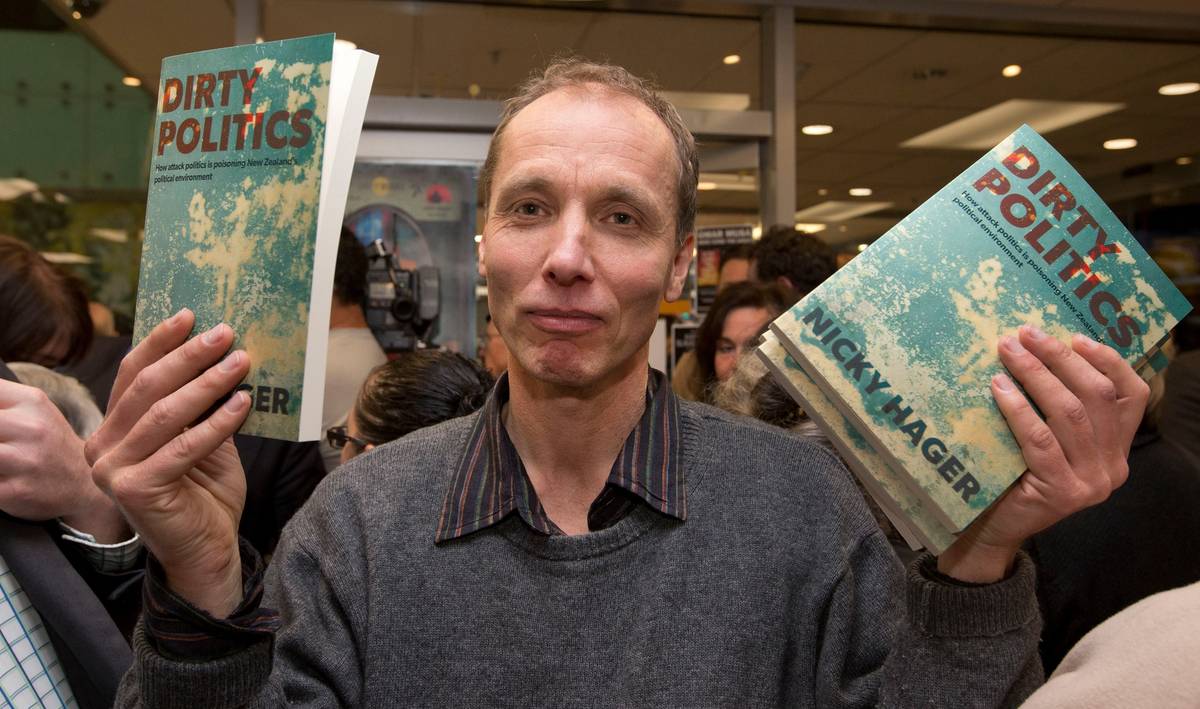

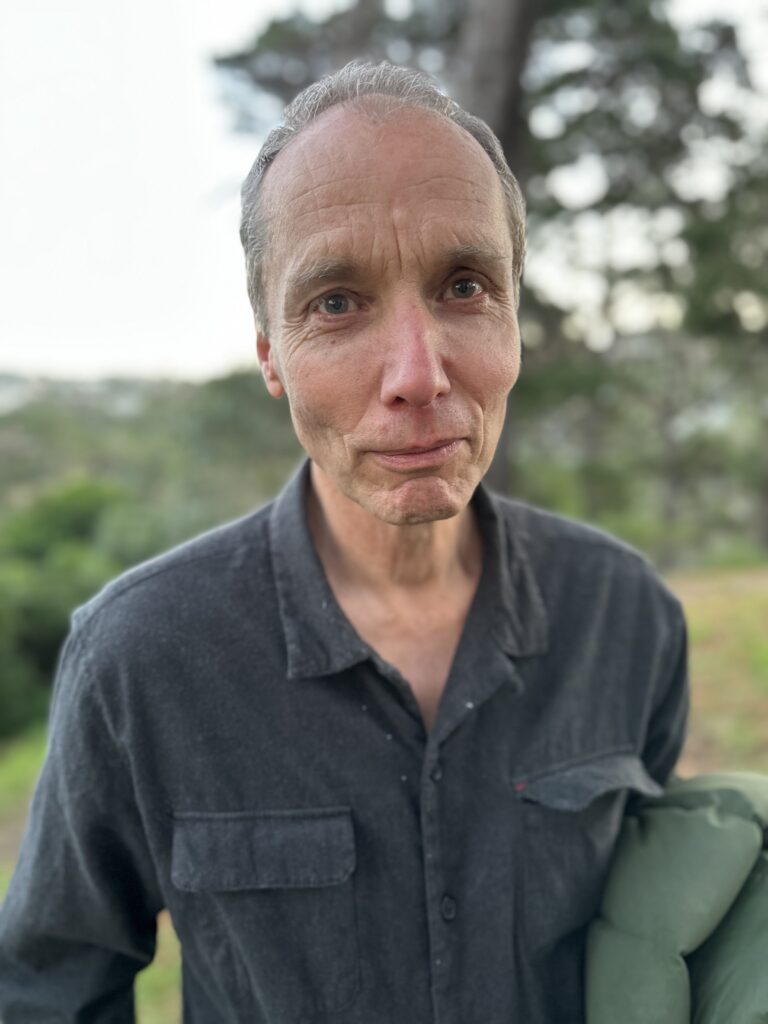

New Zealand author Nicky Hager is a world renowned investigative journalist who has challenged many aspects of his country’s political and military establishments.

His article for Declassified Australia in February 2022 detailed Australia and New Zealand spying in the Pacific. It remains one of our most popular stories.

Hager was a keynote speaker at Dataharvest, the European Investigative Journalism Conference in 2022, and highlighted the big issues needing urgent and lasting media attention. Here is an edited extract of his speech. Part 2 will follow.

The last 10 or so years have been the era of the spectacular leaks. I have worked on various of these: the big Wikileaks leaks about a decade ago, four tax haven collaborations and the Snowden leak, which were shared out around investigative journalists in different countries to find interesting stories. I have gratitude for the leakers and also for the people who facilitated the leaks.

But the first thing I want to say today is that I wonder if these spectacular leaks have created a distorted view of what investigative journalism is about and how it is done. I enjoyed and appreciated these leaks, but almost all the most important projects I did in that decade were other work. As a model for someone coming into investigative journalism I think it is giving an unhelpful picture of what investigative journalism is about.

For a start, there’s no reason why the latest leak will be on a subject that is or should be a priority for us in these times of trouble. For instance I have personally spent years on tax havens. They really matter. But are they most important? With big leaks, we’re suddenly working on tax havens or international spying, when the world might need us to be doing completely different things.

Also we don’t want it to seem as if investigative journalism can only happen with a mega-leak. Most investigative journalism follows a completely different path, using a multitude of other tools.

I also don’t like “biggest leak ever” and “largest collaboration ever” type journalism as a way of grabbing attention. We all know that a big leak may be boring while a small leak, or even just a crucial tip off, might be world changing. It sounds like getting a spectacular leak is the pinnacle of investigative journalism but it is not.

A better approach is to choose the issues where we are most needed and get to work on them. That is where most of our efforts should go.

The first and crucial step in our processes is deciding what most needs our work. We investigative journalists are not technicians; we have acute observation powers and instincts. One of the main things we bring to our work is that we think about and care about issues. We have strong opinions (strong and hopefully well informed opinions). We recognise problems that others aren’t thinking about. We are offended by immorality and deceit. Our first great power is that we can decide which things we want to work on. Having made that decision, almost mysteriously, opportunities often start appearing and things start to happen.

When I decide I’d like to be working on an issue, I call it “putting it on my List.” Nothing great may happen for a long time. But even when I’m busy on other subjects, the act of putting it on my mental list starts it working away in my mind.

The next step is working out, for this issue, what we’d most like to find and what questions we most want to answer. This sounds obvious and easy. But sometimes, in large and multi-faceted issues like climate, politics and war, it is crucial to ask ourselves what information, if we could find it, would most make a difference.

The third step is about mapping out all the possible sources of information: insiders, former staff, open sources, leaks and the rest. I always enjoy this, where it starts off feeling like there are very few options and then the idea-list gets longer and longer. What organisations and companies hold information we are looking for? What are obscure published sources? Field work. Social media tools. Existing data sources we can use again. And much more. The art here is to be creative, stretch out the possible options as wide as possible.

Step four is very practical: breaking down all the ideas so far into a To Do list: call this person, find this kind of person, do these FOI requests, spend an evening searching this subject, visit the specialist library and so on. I find that forming the To Do list can make all the difference. Even when I’m busy on other projects, I find that just having thought through the To Do list means I find time to write the information requests and visit the library. I hear about people who might be worth approaching. People in New Zealand ask me why whistle blowers so often come to me. I reply that they nearly always don’t come to me. I go to them.

I have a personal saying, from back when I interviewed many intelligence staff for my first book, that all the information in the world is accessible somehow; it just has a price tag of hours on it, meaning how much effort and persistence is needed to get there.

Step five is analysis: rereading, sorting and processing the interview notes and other data we’ve gathered; and looking for clues and leads. This can be the stage when we suddenly understand what we’ve found. There’s a subtle but crucial aspect to how we should view each piece of information we’ve gathered. A daily journalist sees them as potential components of a story; we should see them as clues, leads or pointers to information sources to be leveraged to take us further. Any time I read documents, I jot down a follow-up list of the clues and leads revealed and To-Do items for following them up.

One, two, three, four, five: these are the tried and true steps of how we can make a difference in this role. They work over and over again. Of these steps, the most important is us deciding what needs investigating. In a time like now, of multiple troubles, it matters immensely that we focus on the work that is needed most. I am of course not saying that spectacular leaks can’t be worthwhile. But we can’t wait for them on subjects that matter and in fact there is usually more power and achievement from the work we do using the well-established processes of investigative journalism I’ve been discussing.

This leads to my next subject: talking about the troubles we face.

The depressing subject of war

I want to acknowledge first that this is a raw and painful subject, where people you know may have been harmed or be in danger. Wars are the worst breakdown of human civilisation, unleashing terrible things.

I have spent over half of my work time in the last 20 years investigating war. For all that time we have been living through a series of wars. Considering how profoundly terrible they are, there is usually nowhere near enough solid investigation and writing. I think it is vital that investigative journalists prioritise this area of work, not leaving it to on-the-ground war reporters who mostly have different skills.

With the current war in Ukraine, you are all closer and probably more engaged than me. So I will make some more general observations about war as a subject for investigative journalism.

First, it is very hard to report accurately in the midst of the fighting and the media’s need for instant daily news makes it easy for propaganda to be spread. Then, when the fighting is over, most media quickly move on. The stories put out by military PR people frequently become the accepted truth.

This is why the kind of slow work we do is so necessary.

My repeated experience is that militaries feel they have a licence to say what suits them, or what enhances their reputation, but not a requirement to tell the truth. There are decent people in the military, as with any profession, but the organisations believe they have a right to hide things that the public or politicians would not support. I have military documents where so-called “media operations” were a sub-set of psychological operations, where the reality of the war was deliberately hidden to achieve the operational goal of continued government and public support for a deployment. We should always assume that vast amounts of what happens during a war is successfully kept secret, despite the public interest in it being known. It still needs to be found out.

Therefore, a lot of the work begins, not ends, when a battle is over.

Once we have time and apply ourselves, there are 1000s of present and former military staff and other rich sources to be found. I wrote two books on the Afghanistan War, which I recommend to you not to see the text, but to show the endnotes that reveal the fantastic diversity of sources that can be found. Indeed, my experience is that a lot of military secrecy is cosmetic; they’re not very good at it. A determined investigative journalist can find out huge amounts.

One such resource, that I have used repeatedly in the study of war and foreign policy, is the US military and State Department files released and made permanently accessible to us all by Wikileaks. If you’re not familiar with this resource, be aware that amazing riches of detail await you there. And spare a thought for Julian Assange, who is being pursued and punished for precisely this work and deserves all the support we can give.

It doesn’t matter if we are reporting on things that happened years before. Transparency and accountability are better late than never. One of my Afghanistan books was about civilian casualties during a night-time raid led by New Zealand soldiers, years after it happened. It still got plenty of publicity (including the head of the military saying there hadn’t even been a raid) and led to a two and a half year government inquiry. The inquiry called the New Zealand Defence Force’s actions, hiding information and misleading ministers, “deeply troubling”. Revelations about wars and war crimes luckily don’t tend to date.

War is often represented in black and white terms but usually it is murky. Both sides will be culpable and both need our attention. But also there’s a very practical reason for looking at what “our” side is doing, since this is where we have the greatest chance of affecting constructive change.

We also need to be careful not to join in war propaganda. You will have seen that Chinese leader Xi Jinping is called a New Hitler. So too of course is Vladimir Putin. And before them so were the New Hitler Saddam Hussein in Iraq and the New Hitler Gaddafi in Libya, both also Madmen, each of them demonised before being deposed and killed.

It is typical of war propaganda that the enemy is personalised to one individual and then characterised as crazed, isolated and yet another New Hitler. The opposite of a cartoon-like bad guy is where we provide context: history, politics, economic interests, Great Power manoeuvring, the opinions of the local people; the points of view of all parties. The more we study the context of a conflict, the closer to the truth we will be.

As I said, there are good reasons to focus on our own countries and allies because that’s where our governments are responsible. The country responsible for the most wars and coups, the country with the largest military spending, and with the most offensive military equipment, the most foreign military bases, the most international spying and the most arms sales of any country on earth, as we all know but rarely say, is the United States, long-term ally of your countries and mine.

We have a special long term responsibility to investigate all these things and the alliances that tie us to them. This should include investigating the role and operations of foreign military and intelligence bases; what major equipment like aircraft carriers is being used for; the military strategies and war planning; the alliance links and what joint exercises are practising. Also “interoperability”, a boring-sounding word that means continuously preparing our countries to go to war alongside the US and UK, including in the coming resource wars. And, of special importance to us, the control and funding of journalism by these countries, including ensuring that we don’t get caught up in it. We also have a responsibility to investigate the dirty secrets from past wars and military activities.

There’s far too little work going on to monitor and reveal these things. It is all crying out for more investigative journalism.

Also it dismays me that the current war in Ukraine may have a lasting result of a more US-dominated Europe and a renewed Cold War. Looking from the South Pacific, I see the EU, for all its faults, as a reservoir of respect for rule of law, human rights and the United Nations. If the independence of Europe is weakened, it affects is all.

The growth of the far right

For years I have watched the growth of the far right in Europe with alarm. This is for your sake and, as I said, because other countries such as mine rely on a stable, democratic Europe.

In recent years we’ve had two bad experiences in New Zealand of the growth of the far right, both apparently foreign-inspired. The first was a bloody attack on two mosques by an Australian far right fanatic and then just this year a US-inspired protest against covid policies that was used as movement building for the far right.

The protest was in February this year, when New Zealand anti-vaccine groups staged an action imitating the Canadian “freedom convoy” truck protest. Hundreds of people took over the Parliament sector of the city for four weeks, with effigies of people in nooses and being guillotined, and slogans about executing the Prime Minister. It had an ugly ending with protesters pelting the police with rocks and setting their tents on fire.

The most chilling part was the social media statistics. They revealed that more people were getting news about the parliament protest from right-wing and conspiracy social media than from all the mainstream news media combined. The “mass” media was out-massed. It was unprecedented in New Zealand, showing the danger of on-line propaganda. There’s been talk for years about what happens when whole sections of society are detached from mass media and here were some of the consequences.

I mention this story because it is a microcosm of worse things happening in many other places. Personally, I have decided I need to do work on these essentially fascist movements. I’ve put it on my list. You may already be working on this too. It is a dark cloud and there’s urgent work to be done.

This also raises an interesting issue. As investigative journalists, a lot of our work centres on critiquing governments and uncovering things that they would rather have hidden. There is a risk that this can feed straight in to the narratives of the conspiracy theorists and far right: that governments and politicians are all corrupt, that they’re all just as bad as each other, that they are controlled by powerful forces. This is dangerous when the legitimacy of democratic government is already under attack on various fronts.

I don’t think there is a simple answer to this, but I believe that part of the solution lies in our approach. When we expose wrongdoing, we are implicitly calling for a better world. Our currency needs to be hope, change, and improvement, not outrage and disengagement. We need to be careful of our approach and framing, but we also still need to carry out our role of holding governments to account, despite the activities of the far right.

Also, I want to mention a positive story about our parliament protest. During the protest there was a lot of excellent research done, particularly using the massive amounts of social media video and chatter. Good work was done by some journalists but the exceptional work was done by two non-media people who reported on what was being said and done in the protest hour by hour. One was a university researcher and the other an anti-fascist campaigner.

This raises another important issue about our work, which is that some of the best investigative journalism is done by people who aren’t working as investigative journalists. It can be documentary and podcast makers, retired specialists, academics, the Amnesty researcher on surveillance or Greenpeace researcher on fisheries, and so on. I think we need to avoid professional snobbery and be willing to work with anyone doing good work, sharing skills and collaborating with them. They are our natural allies.

–

Before you go…

If you appreciate Declassified Australia’s investigations, remember that this all costs both time and money. Join over 5,000 followers and get our Newsletter for updates. And we’d really appreciate if you could subscribe to Declassified Australia to support our ongoing work. Thank you.