When the AUKUS nuclear-powered subs deal was made public in September 2021 by then Australian PM Scott Morrison, Indonesia reacted quickly.

Jakarta officially stressed it was ‘deeply concerned over the continuing arms race and power projection in the region’. Local academics added the decision has ‘left Indonesia jammed between two major powers [which] could increase tension in the region.’

Indonesian President Joko ‘Jokowi’ Widodo ‘repeatedly and forcefully’ raised concerns about the new AUKUS military pact with Morrison, the ABC reported at the time. Foreign Minister Marise Payne dashed off on a placatory visit to Indonesia and other regional centres.

All this should have been a lesson to stay onside with the neighbours. A wisdom deeply embedded in Canberra is that Indonesia is not to be ignored. Yet that’s what’s happening again with Australia’s latest defence statement. It is either sloppy policy or contrived indifference.

The Defence Strategic Review (DSR) announced by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese in April ‘sets the agenda for ambitious, but necessary, reform to Defence’s posture and structure’.

Ahead of the release, many wondered if the bogeyman would be a hint or a nation. It’s China, with nine references. Mentioned honourably 38 times is our United States protector.

Security analysts and defence academics concentrating on what’s in the DSR haven’t noticed what can be seen clearly across 112-pages: There’s no mention of the world’s fourth most populous nation – inadvertently bang in the middle should the Titans clash.

Check the map

Australian defence planners may be snubbing Indonesia because they’re waiting to see who’ll be the next president. If disgraced former special forces commander Prabowo Subianto scores with his third jab at the top job next February, it’ll be back to the war room.

Prabowo is a migraine for the West. He’s prone to make wild assertions, deny election results, turn out violent mobs and confuse a sci-fi novel for facts – Indonesia’s Donald Trump minus the bone spurs.

His dark past includes allegations he was directly linked to killings in East Timor in the 70s and 80s. In 2000 he was denied a US visa to attend his fashion designer son’s graduation. He told Reuters in 2012 he still couldn’t get a US visa, due to accusations that he was behind riots that killed hundreds after the fall of former dictator Soeharto in 1998.

That didn’t seem to bother Beijing. In December 2019 Prabowo visited China as Defence Minister scouting for arms. Within a year the US visa ban mysteriously disappeared and Prabowo was in Washington with a formal invitation in his pocket from then-Defense Secretary Mark Esper.

A Pentagon statement said the two men met ’to discuss regional security, bilateral defence priorities, and defence acquisitions … Both leaders shared their desire to enhance bilateral military-to-military activities and work together on maritime security.’

Size matters

Indonesia is the world’s largest and most important archipelagic state according to Singapore-based ocean-law academics, Dita Liliansa and Robert Beckman.

They explain that the sprawling mass of 18,000 islands, with 6,000 occupied, ‘sits as the fulcrum between the Pacific Ocean and the Indian Ocean … Passage through and over the Indonesian archipelago is critically important to naval powers and maritime commerce.’ On one estimate, this trade is worth US$5 trillion a year.

Whatever factual or fictional enemy plans to power its landing craft onto deserted Australian beaches would need to navigate a couple of geographical hazards.

The Sunda Strait between Java and Sumatra is so narrow that there’s occasional talk of it being bridged. It’s the site of a fierce night battle in 1942 where the Allies failed to halt an advancing Japanese fleet.

On the sea floor rest the cruisers HMAS Perth and USS Houston, six other ships and the bones of more than 1,000 sailors.

To the northeast is the Makassar Strait – the locale of another 1942 sea fight also won by the Japanese. It’s between Sulawesi and Borneo, the island dominated by the five Indonesian provinces of Kalimantan. This ocean portal leads down to the Lombok Strait between that island and Bali.

It’s not just rude but a serious policy error to take Indonesia for granted. In 1978 and again a decade later, Jakarta closed both straits, reportedly to ‘assert its sovereignty over two of the world’s most important maritime choke points’.

The shutdowns breached international law, but precedents had been set.

Buy now, manage later

The Albanese government has reacted to the Defence Review by allocating AU$19 billion to buy longer-range ‘precision-strike missiles’ so we can knock out the invaders before they arrive.

It’s being sold as ‘forward defence’, ‘impactful projection’ and ’strategy-of-denial’, a dramatic glee-to-gloom turnaround from the previous Labor government’s Australia in the Asian Century White Paper.

In 2011 Australian PM Julia Gillard agreed to the US Force Posture Initiatives allowing the greater opening of Australian bases and ports to US military use.

At the 2012 White Paper launch, Gillard spruiked trade and education, ’nurturing deeper and broader relationships’. Her speech made no mention of ‘threats’ and ‘defence’, though these terms are in the White Paper.

She pushed ‘an ambitious plan to ensure Australia will emerge stronger over the decades ahead, by taking advantage of the opportunities offered by the Asian century.’ It was an advance on the earlier Keating doctrine ‘that Asia is where our future substantially lies.’

The 2023 Defence Strategic Review means sinking ships and killing people way outside Australian territory. It would be impossible to quarantine nearby states from any conflict, so the region has to be involved.

Australian Defence Minister Richard Marles acknowledged this in his Defence Review statement, though more as an afterthought than the prime goal:

‘Australia will also strengthen engagement with Indo-Pacific partners…to maintain peace, security and prosperity in our region. This includes working with key regional institutions, including the Pacific Islands Forum and ASEAN.’

The document asserts that these two agencies ‘remain critical to Australian engagement in the region. Australia’s refocus will continue to rely on such forums as reliable avenues to jointly engage partners at a regional level.’

The problem here is that the ten-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations is not ‘a reliable avenue’ but a potholed dead-end lane, a Cold War anti-Communist relic now incorporating Vietnam and Laos, plus authoritarians like Brunei and Cambodia. Indonesia is the current chair.

In September 2021 FM Payne saw ASEAN as a way for Australia to be more Asian than Anglo because of its ‘centrality, openness, transparency, inclusivity (as) a rules-based region’.

Her flawed ill-timed statement was delivered seven months after the Myanmar coup in February 2021. It has been made nonsense by the consensus-bound ASEAN states’ inability to halt the Tatmadaw’s destruction of democracy and the genocidal civil war.

Boosting the range

Australia’s Defence Department says the missiles on its shopping list will be the US High Mobility Artillery Rocket (HIMARS) systems which ‘currently have a range of up to 300 kilometres which is expected to increase with technological advances.’

There are already rockets on the market, like the Tomahawk with ranges beyond 1,000 km. The distance from Cape York (Queensland) to Merauke in Indonesian West Papua is only 340 km, but for bigger centres like Darwin to Kupang, it’s 830 km.

Weapons that can be installed on the Virginia-class subs (aka SSN- 774) on order through the AUKUS deal are related to long-range intercontinental missiles.

In an earlier attempt at forward defence planning, the perceived menace was Indonesia with left-wing President Soekarno threatening the federation of Malaysia. In 1963 the Menzies government ordered 24 US F-111s because they could reach Jakarta, open their bomb bays and get back to Oz.

Like the AUKUS deal, they weren’t delivered for a decade and by then the new pro-Western kleptocrat Suharto was in power. However, the F-IIIs came close to action following the 1999 East Timor referendum which gave the province independence from Indonesia.

Jakarta was furious and allegedly threatened the post-poll INTERFET peace-keeping force led by Australia.

A Sydney Morning Herald report revealed the F-IIIs ‘were ‘bombed up’ to knock out Indonesian communications as far back as Jakarta’ should Indonesian forces interfere in the operation. That didn’t happen and in 2010 the F111s were replaced by Boeing FA 18 Super Hornets.

Now the supposed threat is not from, but through, Indonesia.

The problem for defence planners is getting Indonesia to partner. That’s not best done by ignoring a nation acutely sensitive to any reminders of Dutch colonial arrogance and conscious of its importance as the world’s third-largest democracy.

The Republic’s passionately held mendayung antara dua karang (rowing between two reefs) policy first revealed in 1948 means it won’t side with world powers.

We should be grateful. If Chinese H-20 stealth bombers (range 8,500 km) were stationed in the archipelago they could hit Canberra and return.

The potential to lob high explosives across Indonesian territory from Northern Australia land bases, or AUKUS subs confronting aggressive foreign navies, is already being considered. That’s reason enough to bring into the fall-out shelter those under flight paths or subject to collateral damage.

If reluctantly forced to back one antagonist through an international crisis, Indonesians would probably choose the US, an assessment based on 2021 research by the Lowy Institute think-tank though neither nation would win any talent quest among the locals:

‘They are increasingly sceptical about China, and particularly of Chinese investment, but neither are they overly enthusiastic about the United States.’

Base issues

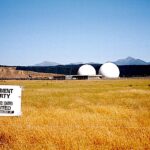

Even before the Defence Strategic Review, the Washington marriage had been well consummated. An American defence policy website claims the ‘US military already has at least seven installations in Australia.’

That number gets expanded to 34 according to the Australian Anti-Bases Campaign Coalition. The government says these are ‘facilities’.

Then there are the US Marines on rotation in the Northern Territory, a deal struck by Labor in 2011. The latest known figure is 2,500 soldiers, with talk of expansion., to 5,000, and beyond.

Last year the US said it would deploy six nuclear-capable B52 bombers through Australia, though this has not been directly confirmed by PM Albanese.

So far the Defence Review has been barely noticed publicly in Indonesia because it was launched at the end of the Islamic fasting month and the start of the week-long Idul Fitri celebrations. Businesses and offices closed as millions quit Jakarta for their hometowns.

Even when back at work this month, the worries will be less about international hypotheticals and more concerned with domestic certainties – the upcoming elections.

There’ll be massive and widespread shake-ups following the Constitutionally compulsory end in 2024 of Widodo’s largely benign rule of two five-year terms.

A re-write of the Defence Review, for the new incumbent in the Presidential Palace in Jakarta might be an intelligent way to improve relations with the neighbours – if that’s what Australia wants.