Australian mining billionaire Andrew Forrest wants to make himself a champion of ‘green energy’ by building an US$80 billion mega-dam to develop ‘green’ hydrogen in one of the world’s poorest and war-ravaged countries.

The Fortescue Future Industries’ plans, if they go ahead, are feared to have significant irreversible social and environmental impacts on indigenous people and communities.

Local land-owning communities in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), who would welcome development and cheaper power, have already come up against the project’s secrecy. They say they are being sidelined and divided, and their voices and community needs prevented from being heard.

Fishing communities, that depend on the river planned to be dammed, are already suffering water level drops from increased drought. It seems fixing the world’s climate change problems with green hydrogen will not be victim-free. Green hydrogen has become a multi-billion dollar gamble by some of the world’s biggest investors and polluting miners.

Declassified Australia has been told by sources in the DRC that locals in the affected areas have been left in the dark about the company and government’s intentions. They’ve been given no guarantees of support or relocation and they fear having their land taken away.

The parallels with Fortescue’s impact on indigenous land-owners in Western Australia are alarming. In 2017, the Yindjibarndi people of the Pilbara area, following a years-long fight against Forrest’s plans for massive new iron ore mines, won a court case that finally granted them access to their cultural sites and a guaranteed community income.

But Fortescue baulked and tried to fight them in the courts. Negotiations between the two sides broke down in 2021 and today Yindjibarndi Aboriginal Corporation chief executive Michael Woodley is still demanding compensation for mining on their land.

Forrest is facing a growing chorus of criticism over his company’s practices, especially with indigenous communities, even prior to this new mega-venture in Congo.

This latest story on Forrest in the DRC follows Declassified Australia’s recent investigation into Fortescue’s interest in mining rare minerals in Afghanistan before the Taliban took control in August 2021. The company has signed similar deals to develop green hydrogen in Indonesia and Papua New Guinea.

Moving into the Democratic Republic of Congo

Forrest’s zeal for DRC accelerated from the first year of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 when the country was one stop in his close to 50-nation visits to make Fortescue a major player in worldwide green energy.

Australia’s second richest person came to the DRC in September 2020 to sign an agreement with the African country’s government to examine the viability of developing hydropower and a hydrogen export facility.

Forrest arrived with a team from the company he founded. The scope of the work was extraordinary; Forrest wanted to build the Grand Inga hydroelectric power and hydrogen-generating project that was slated to be the largest of its kind in the world, double the size of the globe’s current biggest, China’s Three Gorges dam.

Although it had been previously agreed by the DRC that a Spanish consortium and the China Three Gorges Corporation would build the project, Fortescue quickly became the favoured candidate. This was despite the Chinese company being by far the most likely option, as they had previously built the world’s largest dam in the Three Gorges in central China.

Declassified Australia has been told by sources in the DRC that the deal was negotiated without an internationally recognised tendering process.

An official statement from Fortescue Future Industries (FFI) explained that it had “entered into a Deed of Agreement with the DRC to conduct development studies into the feasibility of projects using DRC hydropower and geothermal resources to support green industrial operations.”

In June 2021, DRC formally announced that Fortescue had won the contract, a project worth US$80 billion. European financing was a key component due to its desire to produce green hydrogen, a source of environmental energy. Sanctions on Russian natural gas imports after Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 are leading European governments to seek alternative energy sources.

In theory, the DRC deal sounded exciting in the necessary transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy, especially on the African continent with its soaring population.

Fortescue sold an optimistic message, telling the DRC in 2021 that it had chosen the country to become “world leaders in green industrial products…this would be the world’s largest single source of renewable energy and the beginning of green industry development in the DRC.”

The company promised that it would materially benefit the locals with jobs and training, a similar promise made to the Afghan people by Fortescue in 2020: “The project will provide significant national economic opportunity. In partnership with the DRC, FFI will establish training facilities to maximise local community participation in the workforce as part of its support for the development.”

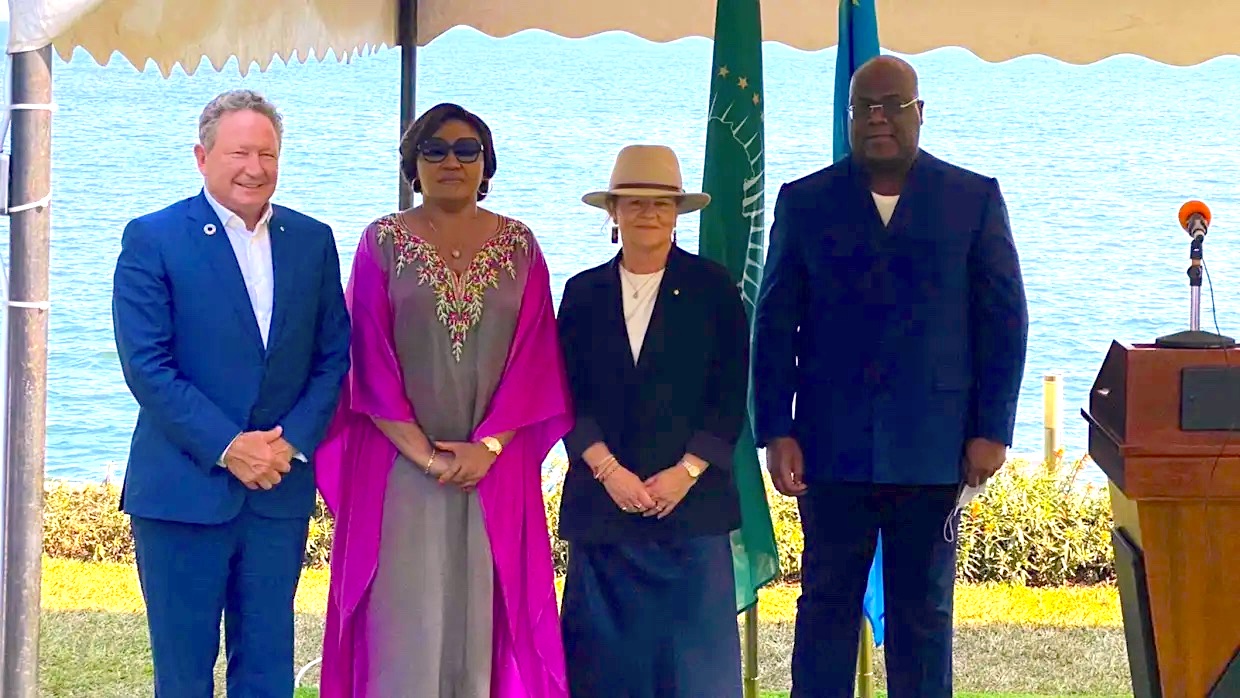

Forrest flew in his $98 million private jet via the new Croatian headquarters of FFI and met the Congolese President Felix Tshisekedi in June 2021 to discuss the agreement. Forrest assured the President that the Inga investment would lead to exporting hydrogen across the world.

“The capital cost of this will be many, many tens of billions of dollars and direct and indirect employment [in the DRC] will be in the hundreds of thousands,” he said.

Fortescue’s dream media run

Australia’s Financial Review (AFR) newspaper gave Forrest mostly supportive coverage though asked some key questions around implementation, namely how the tens of thousands of Congolese inevitably displaced by the project would be adequately compensated or taken care of. No solutions were forthcoming.

In an interview, Forrest told the AFR that his personal relationships with a nation’s leaders were essential “to show solidarity with the country. It is depth of relationship with the administration of countries based on mutual trust.”

Forrest assured readers and investors that, “in every country where Fortescue has secured development rights, it has an agreement with the sovereign leader that should it encounter corruption in any form it will inform the leadership of that country, including the president, who will announce that. And therefore everyone knows from the outset that the entire bidding and construction process will be totally transparent and void of corruption.”

This pledge is hard to square with the reality in Afghanistan before the Taliban takeover in 2021. Corruption of the US-backed government was plain for all to see.

A Fortescue spokesperson told Declassified Australia that it has a “zero-tolerance approach to bribery and corruption; this is reflected within our business integrity compliance framework that has been robustly implemented on a global scale…Any implication that Fortescue is or will in the future be complicit in alleged bribery or corruption associated with DRC would be misleading and factually incorrect. We never have, and never will.”

A further addendum to the contract was discussed with the Congolese government on 30 November 2022 in the presence of Fortescue Future Industries CEO Julie Shuttleworth, who was also present in Kabul for the Fortescue signing in September 2020. Sources in the DRC have told Declassified Australia that many of these proposed contract changes have not been made public.

A Fortescue spokesperson said, “There has been no secrecy about our partnership with the DRC Government. We have been open and transparent about our plans for the DRC green industry project to be one of the world’s largest sources of renewable energy once operating. As we told media in December [2022], we are close to signing an amendment to the 2020 Deed of Agreement and we were in DRC in December working on the final details of this.”

But after months of speaking to environmental and indigenous activists in the DRC and United States, the groups most actively involved in fighting for environmental and civil rights in the DRC, there seems to be a major disconnect between the pronouncements made by Forrest and the DRC government and reality on the ground.

The realities of ‘green’ hydrogen

From the beginning, Fortescue’s entry into Africa’s second largest country was fraught with obstacles. DRC is one of the poorest nations on the planet. According to World Bank figures in 2021, nearly 64 percent of Congolese, close to 60 million people, live on less than US$2.15 a day.

Rare earths such as cobalt are mined extensively throughout the country, a key ingredient in mobile phones, computers and electric cars, while the industry is mired in misery, violence and grinding poverty. Government corruption is rife. During a recent visit to the nation, Pope Francis condemned “economic colonialism” in Africa and the “poison of greed”. Many US mining companies see huge dollar signs across Africa.

Missing from most of the media coverage around Fortescue’s plans in DRC was any serious questioning of the viability of green hydrogen as a climate solution (though there were exceptions). Forrest has been pushing it for years as the best way to solve the world’s climate emergency but organisations who work with the most impacted communities in the Global South argue otherwise.

The US-based group, International Rivers, was founded in 1985 to protect rivers and the communities who need them. In a scathing paper in 2022, the NGO explained that so-called green hydrogen is, “concerning not only because hydrogen produced with hydropower is not ‘zero carbon’ as hydro-to-hydrogen promoters claim, but it would entail significant irreversible social and environmental impacts from biodiversity loss to displacement and impoverishment of people and communities.”

In a statement to Declassified Australia, International Rivers said that, “at a local level in the DRC, FFI is making deliberate and strategic in-roads into Inga communities using a divide and conquer strategy which sees NGOs being side-lined and communities turning against each other due to promises made by FFI to these communities.”

This is backed by sources in the DRC who explain how some communities are promised benefits from the hydropower project while others are not. Fortescue denies these allegations.

A Fortescue spokesperson said to Declassified Australia that the company was “committed to developing this project in the most environmentally sensitive way possible, protecting the ecosystem of the rapids and the river. We can protect the environment while generating green electricity to supply the population of the DRC and to help tackle global warming…The project will be developed in phases, starting with a smaller site with minimum impact. This will allow a step-by-step process to further assess the environmental and social impacts.”

The lost voices of DRC

As soon as the DRC government announced a formal deal had been struck with Fortescue in June 2021, International Rivers wrote that there was a litany of problems with the proposed plan, including ignoring the most immediate needs of the 90 percent of the DRC population who require energy access now (problems that have plagued the country for years).

Furthermore, “Inga would be built over the objections of local communities in a context in which dissent has been stifled and civil society access to the area has been restricted.” Many locals in the impacted areas don’t support the project but their voices are ignored by the DRC government and Fortescue.

Declassified Australia has been told in detail about this after extensive discussions with DRC civil society.

Salome Elolo, director of Femmes Solidaires (FESO), a women’s organisation in the DRC campaigning against the Inga 3 project, told me that a coalition of which her group is a part spoke to the advisor to the DRC President Felix Tshisekedi about Fortescue’s plans. Instead of answering their questions, the presidential advisor suggested that they were unpatriotic and against the President and the country.

Elolo is damning of her government, accusing them of lacking any “vision” around Inga 3 and therefore “quick to jump” towards anyone who comes with ideas about it. Forrest arrived with a huge financial pledge and was seemingly the most viable option.

Elolo explained that, “the villages are still in the dark, with no hospitals or drinking waters and no schools or roads…every question asked by the communities Fortescue doesn’t answer clearly.”

Erick Kassongo is a lawyer and climate activist from the DRC and co-founder of the Congolese Centre for Sustainable Development Law (CODED). Based in the DRC capital, Kinshasa, he told Declassified Australia that he’s been working on monitoring developments around the Inga project since 2013.

Kassongo’s key concern about Fortescue’s plans resolves around the “integrity” of the Congo River, a key element of any hydropower enterprise. Continent-wide droughts are already causing some to question hydropower as a reliable solution but Kassongo said that worsening weather conditions had already led to a “considerable drop in water levels with the first two dams [Inga 1 and Inga 2, with Inga 3 the large, undeveloped dam] which is not without consequences for the fishing communities that depend on this river.”

Kassongo noted that it was impossible to determine the exact scope of Forrest’s plans because the impact studies had not been shared publicly.

When asked directly if the public could see these reports, a Fortescue spokesperson told Declassified Australia that, “the impact studies will be developed with local and highest international standards and guidelines.”

The CODED co-founder said that he had visited the centre of the Inga sites and was worried about what he saw. He claimed that the project was “not being developed in compliance with international standards or with certain laws of the DRC. For such a large project, the circle of institutional stakeholders is too small to inspire any confidence.”

His concerns revolve around the secretive contract bidding process and the affected communities not being consulted before a foreign company signed a deal on their land.

Crucially, Kassongo says, the communities in the impacted areas are “afraid of their futures and not properly informed of their fate. They are even subject to threats, influence peddling and corruption, forced to say ‘yes’ to the project”.

“Fortescue is dividing the communities by ignoring the vast majority of the population currently living in the area”, he explained.

“Some inhabitants of the affected areas say that they risk having their lands taken away from them without adequate compensation, as was the case of one village, Makuku Futila, that’s landless today because it was expropriated but not compensated.”

Kassongo alleged that Fortescue has been distributing gifts to the customary landowners even though the government has not yet signed any formal contracts with them.

A Fortescue spokesperson told Declassified Australia that, “under the 2020 Deed of Agreement, FFI has undertaken extensive due diligence on environmental and social impacts. Community engagement has been ongoing at the Inga site since day one. The intention is to conceptualise the project in such a way as to minimise its environmental and social footprint and impacts, optimise the benefits for the local communities, and deliver much needed development in the region.”

A shift away from fossil fuels is vital for the future of a sustainable planet. But the proposed solutions to take us there, from electric vehicles to green hydrogen, must not potentially solve problems of the Global North and yet create many new ones at the point of contact in the Global South.