The Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan in August last year has caused the country to implode.

It was already on life support after more than 40 years of war but the swift removal of most foreign aid and implementation of Western sanctions have led to millions of Afghans being on the brink of starvation.

The Biden administration’s recent decision to split the billions of dollars of frozen Afghan bank assets with 9/11 victims will not alleviate the suffering.

Women’s rights are being highly impacted. The United Nations now says that only two percent of the population is getting enough to eat. Tens of millions of people can’t support themselves or their families. The harshest drought in 30 years is worsening an already disastrous winter.

However, the humanitarian crisis is just one of the disturbing elements of this long-running catastrophe.

A joint Declassified Australia-Declassified UK investigation has found that resource companies from Australia, as well as the US and the UK, tried to access the war-torn nation’s estimated US$3-trillion of undeveloped minerals in the years after the US-led invasion in 2001.

One huge Australian mining company had controversially stood to gain exclusive access to billions of dollars of Afghanistan’s mineral wealth, in a deal that seemingly evaporated with the fall of the government last year.

Now with the Taliban back in charge, these resources are still up for grabs and yet Western corporations are mostly not in the race to secure them.

Wealth of minerals

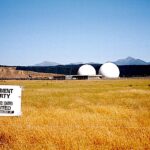

When occupying Afghanistan after its 1979 invasion, the Soviet Union discovered a wealth of copper, iron, lithium, uranium, natural gas and rare earths under the ground but was never able to exploit them.

The post-9/11 occupation saw a new generation of powers aiming to complete what Moscow never could. Washington, London, Canberra, Beijing and private players all vied for influence in the race to discover, mine and export a range of resources.

But insecurity, endemic corruption and political uncertainty in Afghanistan largely caused these plans to fail.

The Afghan ministry of mines was a notoriously corrupt government department. Ironically, the Taliban were one of the very few actors who made money from the mining sector.

I investigated these issues on the ground in Afghanistan in 2012 and 2015 for my book and film, Disaster Capitalism. I found little more than violence and scared civilians in the middle of the Taliban, government forces and militants.

The culpability of the US under successive presidents in promoting the mining sector has been well documented, including the role of Erik Prince, the founder of the Blackwater private military company.

But what about Australia, and the UK, junior partners in the Afghan war?

Australia pushes for influence

Australia’s second richest person, Andrew “Twiggy” Forrest, made his A$23-billion fortune from iron-ore mining in Australia. His company, Fortescue Metals Group, now claims it’s transitioning to green energy and his ambition is vast.

After visiting nearly 50 countries in recent years, Forrest announced in late 2020 that his vision for Fortescue was to become one of the world’s biggest energy providers, one day beating Total and Chevron. He hopes to exploit green hydrogen on a global scale and in Afghanistan was part of the picture.

Forrest visited Kabul in September 2020 with his Fortescue Future Industries CEO, Julie Shuttleworth. Fortescue issued a press release that stressed the development of hydropower and geothermal projects for green industries in Afghanistan as well as campaigns on the eradication of slavery and support of local employment.

In the presence of the Australian ambassador to Afghanistan, Forrest also signed a secret Deed of Agreement with the Afghan government during the visit.

Declassified Australia has a copy of this document, originally obtained by Afghan news outlet Pajhwok, signed on 10 September 2020, that outlines the terms of the agreement.

Fortescue was to be guaranteed exclusive access to vast swathes of the country to explore “mineral deposits [and] mine sites”. It pledged to establish a “vocational training and employment plan that provides equal opportunities between women and men with an explicit equal employment target”.

The agreement would give Fortescue exploration rights till 2025 over “all potential mineral deposits” in the country, the most valuable of which are iron ore, copper, gold, lithium and rare earths. In return, during exploration the company would grant 15 percent of the project budget to the government as a guarantee, an amount totalling many billions of dollars. Following the exploration period, the agreement allowed for mining licenses to be granted to Fortescue “for an indefinite period”.

The deal came as a surprise to many, as over the past 20 years, the Afghan Ministry of Mines had not signed any successful contracts in the mining sector, according to the National Resources Commission.

Fortescue deal questioned

Notably, nowhere in the document did it explain how the mining areas could be secured in the middle of a war zone.

My own reporting in Afghanistan, including on the proposed mineral exploration plans by Erik Prince, show that Fortescue’s plans would likely never have materialised without the support of local militias and warlords to keep militants at bay and wrestle control of resources from the Taliban and Islamic State.

This wasn’t mentioned by Fortescue or in the Australian media coverage of the deal. It was only Afghanistan’s independent news agency Pajhwok that critically assessed the agreement and wondered if it was even legal, since it was signed without the legally-required bidding process.

After the Taliban seized power, Forrest told the militants that, “We would meaningfully engage with anybody, including the Taliban, if they guaranteed equal education outcomes for girls and boys”.

Fortescue’s work in Afghanistan is currently “on hold”, a company spokesperson told Declassified Australia. Fortescue had only one employee based in Afghanistan, who had departed before the Taliban retook Kabul.

The Taliban ignored a request for comment for this article on its present mining policies.

Australian safe haven for senior Afghan officials

Australia evacuated around 4,100 people from Kabul in August and now claims to be offering 15,000 places for Afghans under a humanitarian short-term protection visa. But human rights activists and immigration lawyers claim that this number is misleading.

At the time of writing, Australia hasn’t granted a single protection visa – but Declassified Australia has learned Australia has granted safe haven to a number of Afghan officials.

One of the Afghan signatories on the Agreement signed by Andrew Forrest in Kabul in 2020 was Mohammad Haroon Chakhansuri, former Minister of Mines and Petroleum under President Ghani.

Declassified Australia can reveal that he has been living in Sydney with his family since the fall of Kabul, and is receiving Australian government assistance. When Chakhansuri was approached in Sydney for comment on this article, his brother Humayoon explained he was “not yet ready to discuss anything”.

Another new arrival in Australia is Mohammad Ateeq Zaki, a former Deputy Minister at the Afghan Ministry of Mines and Petroleum.

General Murad Ali Murad, Afghan National Army Deputy Chief of Staff and Deputy Interior Minister for Security, is also now in Australia. He was no doubt helped by positive comments he made in Kabul in 2018 to Australian forces in Afghanistan: “Afghanistan will never forget the help Australia has given.”

Diaspora Afghans have expressed disquiet to Declassified Australia about Western nations providing safe haven to former Afghan government officials. There have been many serious allegations of corruption against the Ghani regime. Declassified Australia is not making any allegation about people mentioned in this article.

The New Zealand government is facing a similar crisis over vetting of Afghans it brought into the country after the Taliban takeover.

Afghan mining goals dashed

In 2015 when I visited the area near a proposed copper mine at Mes Aynak in Logar province of eastern Afghanistan, locals were on the verge of joining the insurgency because they’d received nothing in return for their land being stolen.

The British Geographical Survey (BGS) had helped the Afghan government prepare to take tenders to develop the mine at Mes Aynak, one of the world’s largest untouched copper deposits valued at around US$50-billion.

BGS had worked in Afghanistan from at least 2004 to “develop a viable minerals industry”. It said that “as the project progressed, the emphasis of the work moved to promote the potential of Afghanistan’s mineral resources to the outside world.”

A 2007 report by BGS funded by the UK Department for International Development in 2007, tackled “the need to alleviate poverty in Afghanistan by encouraging inward investment, commercial and infrastructure development”.

A part of this plan was providing “an alternative source of income to poppy cultivation” in the mining sector. It claimed that a successful resources industry could net “at least US$300-million a year”. But it didn’t state for whom: local Afghans or international mining interests?

BGS proudly wrote that it had helped prepare a new mining law in 2005 that would “enable it to effectively and efficiently manage an emerging mining industry”. There’s little evidence that this law prevented corruption. In fact, several cases suggest the opposite.

The BGS assistance to the Afghan government to prepare for tenders to develop the copper deposits at Mes Aynak, showed little result. Eventually in 2008 Beijing was granted the contract for the mine, but the project has been beset by violence and corruption, and after over a decade has not proceeded.

Despite a litany of similar failures, London didn’t give up. British prime minister David Cameron pledged £10-million in 2013 to exploit Afghan minerals, and Downing Street hosted visits by mining interests – but the wining and dining didn’t get far.

The United States Geological Survey visited Kabul in late 2017 to assess the viability of large-scale mining, and in early 2019 the US government signed an agreement with the Afghan government to assist in the development of the mining sector.

President Trump was initially excited about the prospect of American companies exploiting Afghan resources but this went nowhere beyond twisting the arm of the Afghan government to grant licences to foreign mining companies.

Mining enterprises from the US and the UK, as well as from Australia, landed in Afghanistan with promises of advancement and development, but with the return of the Taliban, it has all been for nought.

What now for Afghanistan’s ‘treasure house’?

“The regime collapsed because of the corruption in the government, and not because the Taliban were strong,” Afghan mining expert, Javed Noorani, told me from the US.

Since the fall of Kabul, US-led sanctions are suffocating the country and some Afghans are using cryptocurrencies to survive. Despite the Taliban’s opposition to poppy cultivation, drug use is soaring while illicit production of the ephedra shrub, a key ingredient in the hugely expanding methamphetamine industry, is booming.

It would seem the only way to credibly address the country’s plight is to engage with and recognise the Taliban with certain conditions around human rights. The fact that there’s no discussion in London, Washington or Canberra about reparations for a failed, 20-year war speaks volumes about how the West views Afghanistan.

A former senior Afghan government official who used to advise President Ghani told Declassified Australia that following the withdrawal of all Western forces, China and Pakistani army officers are currently leading the charge to secure Afghan minerals, with the Taliban auctioning mines for quick financial return. Coal, talc, and the gemstone cat’s eye nephite are the three resources being prioritised.

For the Western media, which was briefly enamoured with Afghans when the Taliban regained control, Afghanistan has largely disappeared from the news cycle.

The humanitarian crisis currently engulfing the country is mostly framed around how it impacts the Western nations that lost the war, rather than on the civilians on the brink of starvation.

Antony Loewenstein is an independent journalist, author, film-maker and co-founder of Declassified Australia. He’s written for the Guardian, New York Times and many others. His books include Disaster Capitalism: Making A Killing Out Of Catastrophe and Pills, Powder and Smoke: Inside The Bloody War On Drugs and films include Disaster Capitalism and the Al Jazeera English films West Africa’s Opioid Crisis and Under the Cover of Covid. His next book, out in 2023, is on how Israel’s occupation has gone global.

This Declassified Australia story has been prepared and co-published in cooperation with the London-based DeclassifiedUK.